Demand grows for rape laws to recognise need for consent

Denmark’s reputation for gender equality masks a society with one of Europe’s highest levels of rape, where flawed legislation and widespread harmful myths and gender stereotypes have resulted in endemic impunity for rapists, Amnesty International said in a report published today.

“Give us respect and justice!” Overcoming barriers to justice for women rape survivors in Denmark reveals that women and girls are being failed by dangerous and outdated laws and often do not report attacks through fear of not being believed, social stigma and a lack of trust in the justice system.

“Despite Denmark’s image as a land of gender equality, the reality for women is starkly different, with shockingly high levels of impunity for sexual violence and antiquated rape laws which fail to meet international standards,” said Kumi Naidoo, Amnesty International’s Secretary General.

“The simple truth is that sex without consent is rape. Failure to recognise this in law leaves women exposed to sexual violence and fuels a dangerous culture of victim blaming and impunity reinforced by myths and stereotypes which pervade Danish society: from playground to locker room, police station to witness stand.”

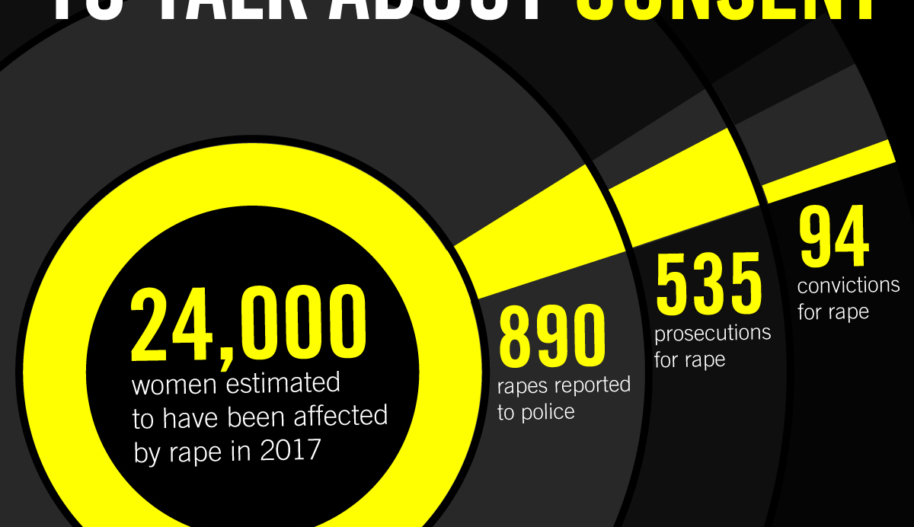

Despite recent steps by the government to improved access to justice for survivors, rape in Denmark is hugely under-reported and even when women do go to the police, the chances of prosecution or conviction are very slim. Of the women who experienced rape or attempted rape in 2017 (estimates vary from 5,100 according to the Ministry of Justice to 24,000 according to a recent study), just 890 rapes were reported to the police. Of these, 535 resulted in prosecutions and only 94 in convictions.

Deeply entrenched biases within the justice system are among the reasons for the low conviction rates. Lack of trust in the system together with fear of not being believed and self-blame are all factors that result in under-reporting.

Harrowing experience

The research, based on interviews with 18 women and girls over the age of 15 who have experienced rape, as well as NGOs, other experts and relevant authorities, found that survivors often find the reporting process and its aftermath immensely traumatizing.

Many are met with dismissive attitudes, victim blaming, and prejudice. Survivors told Amnesty International that the fear of not being believed or even being blamed and shamed by police and justice officials were among the primary reasons for not reporting rape.

Kirstine, a 39-year-old journalist, tried four times to file a report of rape with the police. On her second attempt she was taken to a police cell and warned that she could go to prison if she was lying. She described how the reporting process meant “enduring new fear, shame and humiliation” and told Amnesty International: “If I was 20 years old, I wouldn’t have proceeded after the first attempt.”

Another woman told Amnesty International how intimidated she felt going to the police: “I was just one 21-year-old woman, sitting there with two guys looking at me, saying, ‘are you sure you want to report this?’…I was just a young girl ‘claiming’ to have been raped.”

While there are National Police Guidelines on handling rape cases, current police practice remains inconsistent and often falls short of both these guidelines and of international standards.

The women and girls who do report rape face lengthy journeys through the courts and the experience can be harrowing and deeply unsatisfactory.

Emilie told Amnesty International she definitely would not go to the police if she was raped again. “When they really push me in court, it is almost like experiencing it all over again, and then you end up feeling worse about yourself, feeling like ‘it’s my fault, it was me who did something wrong.’”

Definition of rape based on violence

Under the Istanbul Convention, ratified by Denmark in 2014, rape and all other non-consensual acts of a sexual nature must be classified as criminal offences. However, Danish law still does not define rape on the basis of lack of consent. Instead, it uses a definition based on whether physical violence, threat or coercion is involved or if the victim is found to have been unable to resist.

The assumption in law or in practice that a victim gives her consent because she has not physically resisted is deeply problematic since “involuntary paralysis” or “freezing” has been recognized by experts as a very common physiological and psychological response to sexual assault.

This focus on resistance and violence rather than on consent has an impact not only on the reporting of rape but also on wider awareness of sexual violence, both of which are key aspects in preventing rape and tackling impunity.

Change in legislation needed

The Danish government has recently established an expert group to recommend initiatives that can help rape victims to receive adequate support and professional treatment when they navigate the system. While Amnesty International welcomes these initiatives, the government needs to take much bolder steps and change the legislation to be based on consent.

Although amending current rape laws would be a vital step towards changing attitudes and achieving justice, much more is needed to effect institutional and social change. The authorities must take lawful steps to ensure that rape myths and gender stereotypes are challenged at all levels of society and that professionals working with rape survivors receive adequate continuous training. In addition, broader sexuality education and awareness-raising programmes are needed from a young age.

“By amending its antiquated laws and ending the insidious culture of victim blaming and negative stereotyping that currently exists in legal proceedings, Denmark has an opportunity to join the tide of change that is sweeping Europe. This tide, led by courageous women, has led to eight countries in Europe adopting consent-based rape definitions,” said Kumi Naidoo.

“This tide of change in Denmark and other parts of Europe can help ensure that women are better protected from rape and will mean that future generations of women and girls will never have to question whether rape is their fault or doubt that the perpetrators will be punished.”

For more information or to arrange an interview contact Lucy Scholey, Amnesty International Canada (English): + 613-744-7667 ext. 236; lscholey@amnesty.ca

Background

Amnesty has analysed rape legislation in 31 countries in Europe and found that only 8 out of 31 countries have consent-based legislation in place. These are Sweden, the UK, Ireland, Luxembourg, Germany, Cyprus, Iceland and Belgium.

In the other European countries, for the crime to be considered rape, the law requires for example the use of force or threats, but this is not what happens in a great majority of rape cases.

As activists, including Amnesty, continue to raise their voices for ‘Yes’, Denmark is poised to follow suit and authorities in countries such as Finland, Greece, Spain, Portugal and Slovenia are also considering such changes.

Amnesty will continue to monitor the situation across Europe and campaign for consent-based legislation and challenging rape myths throughout the region. In April 2019, 11 years after its Case Closed report, Amnesty will also publish a regional report on access to justice for rape in four Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden).